T1D Guide

T1D Strong News

Personal Stories

Resources

T1D Misdiagnosis

T1D Early Detection

Research/Clinical Trials

Mariana’s Story: Looking into the Past to Change the Future of Type 1 Diabetes in Mexico

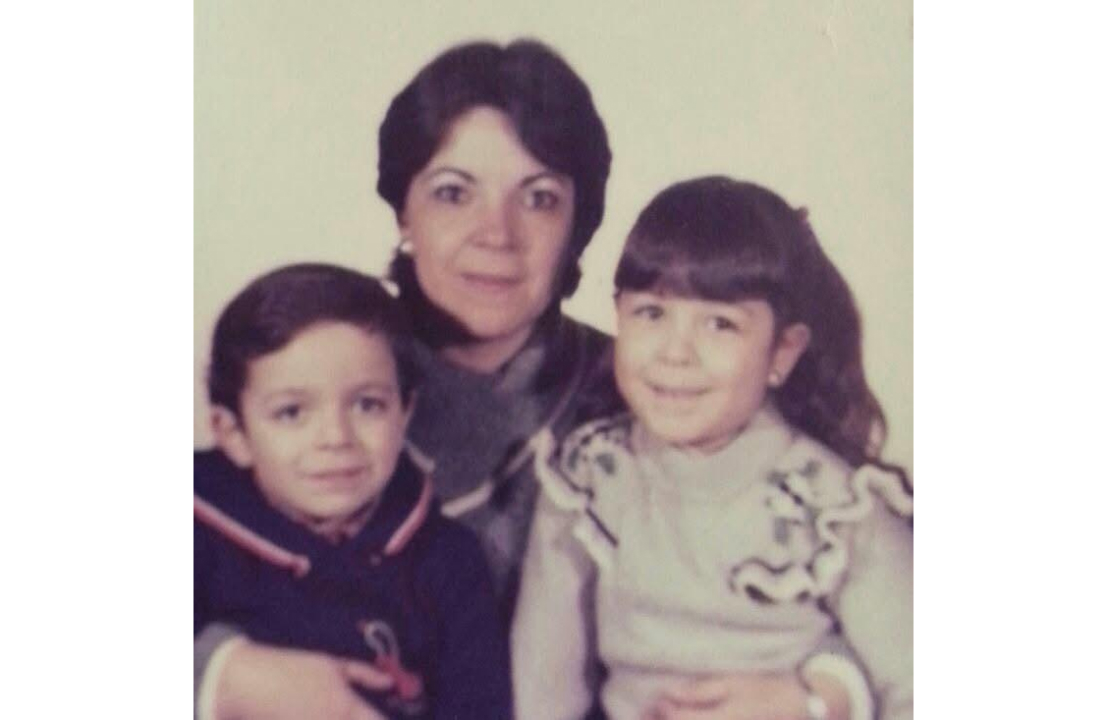

As a child in Mexico City, Mariana Gómez lived with an energy that seemed boundless. She ran, climbed, and danced through her early years, embraced by a close family and an inquisitive mind. At age six, her world changed forever. New symptoms crept in slowly. First, there was an unquenchable thirst. Then came exhaustion that sleep could not cure. Mariana’s parents began a desperate search for answers, visiting doctors and clinics—only to encounter indifference and confusion.

.jpg)

Mexico in the 1980s was a country with little understanding of type 1 diabetes (T1D). There were no public campaigns, no national screenings, and few with experience in this diagnosis. Mariana became one of countless children lost within medical uncertainty.

Unseen Danger: When Every Doctor Visit Brought More Questions

For months, Mariana’s health continued to decline. The family cycled through explanations and misdiagnoses—urinary infections, growth spurts, even lingering colds. But the real source of Mariana’s distress remained hidden. Each new appointment brought more worry, and each day her condition worsened.

She watched her own reflection dwindle with blurred vision staring back and her body shrinking. The girl who once ran and danced now struggled to find strength just to get through the day.

Mariana remembered opening the water tap, desperate to drink, climbing up on tiptoe to gulp water straight from the bathroom faucet. “I always felt so thirsty,” she said. “I remember climbing and putting my head under the tap, needing so much water just to feel normal for a moment.”

These memories remain, despite her mind shielding her from many painful details of that time. The trauma was real, but its sharpest edges have, in her words, faded into a “cloudy” recollection—something not uncommon for children with life-altering illnesses.

A Crisis and a Diagnosis

Everything changed the summer Mariana turned six. Her parents, increasingly alarmed, watched her grow weaker and more confused. Then, one day, Mariana could not be roused.

She fell into a coma.

In the hospital, someone passing by noticed a sweet, fruity smell to her breath. This clue—a classic sign of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening complication of T1D—led to a blood test that revealed the true cause of her decline: dangerously high blood sugar.

For days, as doctors worked to stabilize her, Mariana’s family struggled with fear and uncertainty. When she finally woke, everything was different.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that diabetic ketoacidosis is still a major risk for children whose diabetes remains undetected.

Mariana would later reflect, “My story is one I can tell because I survived. Many aren’t so lucky.”

With a diagnosis came new rules for daily life—insulin shots, food restrictions, and regular doctor visits. But the larger transformation happened within her family: Mariana’s mother became a relentless champion for diabetes education. She spread the message that families should watch for warning signs, that a simple glucose test could save a child’s life.

Mariana’s early years with type 1 diabetes were marked by confusion and resilience. “There is a Mariana before my diagnosis, and a Mariana after. It changed everything,” she says.

Everyday Reality: Growing Up With Diabetes

Returning home from the hospital, Mariana found that nothing would ever be as it was before. School was a challenge. Injections often interrupted her day at recess, forcing her to become an involuntary educator about her disease to classmates and teachers who knew nothing of T1D.

She admits that injections were her greatest fear as a child. Her family, long supporters of vaccinations, had to reframe their entire approach to health. Her mother’s creativity and humor, inventing stories or references to the sea, helped Mariana cope.

Still, the family faced significant emotional and financial challenges. Insulin, test strips, and doctor visits—these were expensive and not always fully covered. The emotional toll was visible, not only in Mariana but in her parents.

Guilt and self-blame are common for families in this position. Mariana says, “My mother once told me she felt responsible for not spotting it sooner. We know now that type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition—we didn’t cause it. But guilt is a powerful thing.”

In those years, Mexico was a place where T1D was rarely discussed. Most people were only aware of the more common type 2 diabetes, creating a sense of isolation for Mariana and others like her. She grew up not just learning to manage blood sugar, but to explain and defend her right to a normal life.

Barriers to Early Screening in Mexico

Looking back, Mariana is certain her story could have been different if screening tools had been widely available.

Early screening for type 1 diabetes, which the American Diabetes Association (ADA) now advocates, is a powerful tool for avoiding crisis and preparing families. But in Mexico, routine screening remains uncommon.

Screening for autoantibodies—the markers that signal increased risk—can identify those susceptible to type 1 diabetes long before symptoms appear. But this testing is rare outside of select city hospitals or private clinics. In most communities, neither ordinary physicians nor the public are aware of these options.

Financial hurdles also abound. Many families simply cannot afford advanced testing. Awareness campaigns are few, and the anxiety surrounding a possible diagnosis often keeps people from pursuing information.

A 2024 survey by a regional non-profit found that over 60 percent of parents and caregivers had no idea screening was even possible. Of those surveyed, 93 percent reported they wished they’d known their child was at risk before symptoms appeared. These numbers, and the accompanying emotional toll, underscore how much work remains.

The lasting impact is not just medical but psychological, as families cope with regret and “what ifs.” Mariana has channeled these experiences into advocacy, calling for broader access and wider education.

The Promise of New Treatments and Early Action

If Mariana’s childhood feels like a cautionary tale, it is also a beacon of hope for change.

Recent years have brought remarkable advances. In 2022, for example, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a therapy—teplizumab, a monoclonal antibody—that can delay the progression from early-stage autoimmunity to symptomatic type 1 diabetes. For many, as research from the NIH and Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF) confirms, access to such treatments could mean valuable time to adapt and prepare for life with diabetes.

Mariana dreams of a day when these innovations reach families in Mexico and Latin America. She imagines parents presented with a choice: to prepare, to educate, to connect with others walking the same path, instead of facing crisis in the dark.

Her own son, now nineteen, faces a higher risk due to family history. Mariana has discussed screening and new treatments with him openly. “He says he’d want to know, and he isn’t afraid,” she shared. “For him, diabetes doesn’t seem as scary or mysterious as it once did. We’ve learned together.”

Lessons Learned and a Message for Tomorrow

Today, Mariana is a psychologist and a leader within Mexico’s growing diabetes community. She advocates for three things above all: national statistics to understand the true scale of type 1 diabetes in Mexico; government investment in universal, affordable screening; and robust support for every person and family who faces this journey.

Mariana believes that knowledge—while sometimes frightening—empowers people. With early information, families can prepare, process emotions, and make financial plans.

She envisions a future where no child in Mexico, or anywhere in Latin America, lacks access to the care, information, and community support that could transform their experience with type 1 diabetes.

“Early screening saves lives,” she remarked. “It’s hope, not just data. It’s the difference between a crisis and a chance.”

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

%20(1).png)

.jpeg)

.webp)