T1D Guide

T1D Strong News

Personal Stories

Resources

T1D Misdiagnosis

T1D Early Detection

Research/Clinical Trials

Diabetes and Hearing Loss: The Invisible Condition No One Talks About

Hearing loss is one of the least-discussed complications of diabetes, yet research shows it’s twice as common in people living with the condition. This story explores how diabetes can quietly affect hearing, what the science says, and how real people are adapting and finding connection through awareness and community.

Understanding the Connection

When most people think about diabetes complications, they picture vision loss, kidney disease, or nerve damage. But the ears are rarely mentioned.

Hearing loss is often invisible and can develop so gradually that people don’t notice until communication becomes difficult. Diabetes, on the other hand, varies. Type 2 diabetes and adult-onset type 1 may progress slowly, but for many diagnosed in childhood — including me — it can appear suddenly, sometimes through a medical crisis like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). However it begins, both conditions can deeply affect daily life and deserve greater awareness.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), people with diabetes are twice as likely to have hearing loss as those without. Adults with prediabetes are 30 percent more likely to develop hearing problems.

How Diabetes Can Damage Hearing

Experts believe both high and low blood sugar can harm the delicate structures inside the ear.

High blood sugar can damage the small blood vessels in the cochlea, the spiral-shaped organ that translates sound into signals for the brain. Fluctuating glucose levels may also affect the nerves that carry those signals. Chronic inflammation, common in diabetes, can injure the tiny hair cells that detect sound.

Other metabolic factors, such as high cholesterol and insulin resistance, may worsen these effects. Elevated cholesterol can restrict blood flow to the inner ear, while insulin resistance increases inflammation and oxidative stress that can harm auditory nerves.

Together, these changes can lead to sensorineural hearing loss, the most common and permanent type. Once the inner ear or auditory nerve is damaged, it cannot be repaired — and the loss often goes unnoticed until communication becomes difficult.

Signs You Might Be Losing Hearing

Because hearing loss is gradual, it’s easy to overlook. Friends or family often notice first.

Common signs include asking people to repeat themselves, struggling to follow conversations in noisy places, feeling like others are mumbling, or needing to turn up the TV or phone volume. Many people also lose sensitivity to high-pitched sounds such as alarms or children’s voices.

Balance issues can appear, too. The CDC notes that vestibular (balance) dysfunction is 70 percent more likely in people with diabetes, and the risk of falls is 39 percent higher.

The Numbers

- Hearing loss is twice as common in people with diabetes compared with those without.

- Adults with prediabetes are 30 percent more likely to have hearing problems.

- Vestibular dysfunction is 70 percent more likely in people with diabetes.

- The risk of falls is 39 percent higher in people with diabetes.

Why Hearing Loss Feels Invisible

Hearing loss rarely happens overnight. It creeps in slowly — a few missed words, a laugh you don’t quite catch, a question answered too late. Conversations start to take more effort, and noisy environments become exhausting.

Because hearing loss isn’t visible, others may not notice. They might mistake the struggle to hear for inattention or disinterest. Over time, that misunderstanding can feel isolating.

When paired with diabetes — another condition that’s largely unseen — the emotional toll can be heavy. Managing both requires constant focus, and the effort can drain even the most resilient person.

Many people begin to pull back from social events, not because they want to, but because it takes so much energy to keep up. That isolation can affect confidence, relationships, and mental health — and even make diabetes management harder.

Experts urge people with diabetes to treat hearing health as part of routine care. Just like eye exams or foot checks, hearing screenings help catch small changes early. Protecting your hearing supports more than just sound — it protects your safety, connection, and quality of life.

Prevention and Management

While hearing loss can’t be reversed, there are steps to prevent or slow it — and to stay connected despite the challenges.

Keeping blood sugar within your target range supports healthy blood vessels and nerves, which benefit your ears as much as your eyes and feet. Schedule annual hearing exams, and get a baseline test soon after your diabetes diagnosis. Protect your ears from loud noise, lower headphone volume, and ask your doctor about medications that might affect hearing.

Early attention matters. Detecting hearing changes now can make a big difference later — not only for communication but also for safety, confidence, and overall well-being.

The Human Side

Living with two invisible conditions can feel isolating. Many people with diabetes and hearing loss report frustration in group settings or fear of missing pump alarms at night. Finding the right tools—and people who understand—can make a big difference.

Craig’s Story

Craig has lived with type 1 diabetes since childhood and began losing his hearing as a young adult. His hearing loss likely stems from years of loud environments, but he sees parallels between the two conditions.

“One shared experience is being tested,” he said. “People question what diabetics ‘can’ or ‘can’t’ eat the same way they whisper or yell to test our hearing. Even if it’s well-intentioned, it’s exhausting.”

Craig said the mental load of managing T1D while adapting to hearing loss is heavy but familiar. “We question everything — every feeling — wondering if it’s because of blood sugar or something else,” he said. “After years of that, it takes emotional energy too.”

He uses vibration and visual alarms to stay aware of his devices, but admits alarm fatigue is real. “The vibrations in my pocket are like water torture,” he joked. “I know it’s coming, but never when.”

Even within the Deaf community, Craig said he sometimes feels judged for not being “deaf enough.” He chooses not to wear hearing aids, explaining that he already has enough medical tech attached to his body. Instead, he’s embraced sign language and Deaf culture as part of his identity.

“It’s not about fixing myself,” he said. “It’s about learning new ways to live and connect.”

Through both the Deaf community and his T1D connections, Craig has learned to view each condition differently. “I used to see deafness as a disability,” he said. “Now I see it as a different way of living — and beautiful in its own way.”

Tools That Help

Managing both diabetes and hearing loss can feel overwhelming, but new technology offers help.

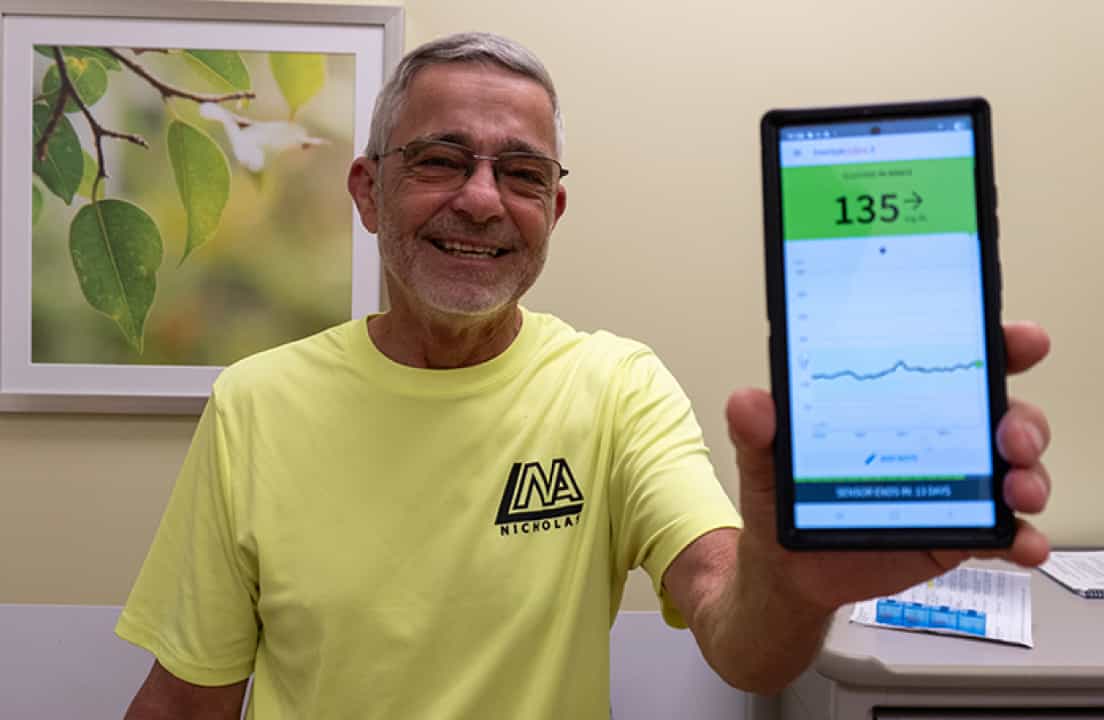

Transcription apps such as Live Transcribe and Otter.ai assist during conversations. Smartwatches can vibrate for blood-sugar alerts when pump or continuous glucose monitor (CGM) alarms aren’t heard. Tools like SugarPixel provide vibration or light notifications overnight.

Some hearing aids now pair via Bluetooth with CGMs or smartphones. Support groups such as Deaf Diabetes Can Together provide education in American Sign Language (ASL) and connect people who live with both conditions.

Theresa’s Story

Theresa was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age five and developed hearing loss around 19. Now 27, she said she often feels doubly invisible — unseen in both the diabetes and Deaf communities.

“In the Deaf community, I don’t know anyone else with T1D. In the diabetes world, few people know sign language,” she said. “I have to constantly advocate for both sides of who I am — and that’s exhausting.”

As a graduate student at Gallaudet University, Theresa studies in an environment designed for the Deaf community. Still, she faces barriers in diabetes care.

“My CGM alarms are sound-based. They’ll wake my hearing partner before they ever wake me,” she said. “Doctors focus on why I didn’t respond to an alarm instead of listening to why I couldn’t hear it.”

A breakthrough moment came recently at a Grownup T1Ds event that arranged for an ASL interpreter who also lived with type 1 diabetes. For Theresa, it was the first time she could fully take part in a diabetes gathering since developing hearing loss — an experience she described as profound and life-changing.

“That day my worlds collided,” she said. “It showed how powerful it is to find people who truly get your experience because they live it too.”

The impact of that experience stayed with her. “I actually spoke with my thesis advisor about changing my research topic to better align with advocacy for the Deaf and T1D communities,” she said. “The conversations I had after that event completely reshaped how I want to approach my work.”

Theresa also feels deep frustration about how little awareness exists around hearing loss and diabetes. “Audiologists and ear, nose, and throat specialists (ENT) don’t know anything about T1D, and endocrinologists rarely look beyond blood sugar and eyes,” she said. “Outside the doctor’s office, there’s just a lack of understanding everywhere.”

Still, she believes change is possible. “You can find people who get you,” she said. “No matter how niche your battle feels, there’s a community out there.”

My Experience Living With Both

For me, hearing loss isn’t just another statistic — it’s personal.

My hearing loss began in my early 30s. By my mid-30s, I finally saw an ENT and an audiologist who told me I needed hearing aids. I resisted at first. I had already been living with type 1 diabetes for 20 years, wore an insulin pump, and felt I had enough medical challenges. Plus, hearing aids were expensive.

When I was tested, I hadn’t realized how much hearing I’d already lost. I saw multiple specialists — ENTs, neurologists, even a cardiologist — trying to understand why. With no family history or loud-noise exposure, I kept asking if it could be related to diabetes. Each time, the answer was no. “It’s just one of those things,” they said.

Years later, I began finding research connecting hearing loss to diabetes. At first, most of it focused on type 2 diabetes, but over time the data expanded to include all forms of diabetes. That validation came with frustration — because deep down, I knew there had to be a link.

I’ve worn hearing aids for more than 20 years now.

Hearing aids don’t fix hearing loss any more than insulin fixes diabetes.

They amplify everything — the person you’re talking to, background chatter, even footsteps or clinking glasses. It can make social settings overwhelming, and people sometimes lose patience when I ask them to repeat themselves.

Before I knew how much hearing I’d lost, there were so many times my insulin pump would alarm and everyone around me heard it — except me. People would look around asking, “What’s that noise?” and I’d shrug, thinking they were imagining things. When I finally got my first pair of hearing aids and heard my pump alarm for the first time, I burst out laughing! It was such a small moment, but it changed everything — proof of how much we adapt without realizing it.

Living with both diabetes and hearing loss means managing two invisible conditions that require constant explanation. Over time, I’ve adapted and made peace with it. Still, I worry about the long-term cognitive effects — memory, vocabulary, and communication skills. Those fears are real.

Even so, my determination to keep connecting, learning, and raising awareness remains strong. My hearing loss may be irreversible, yet my voice isn’t. Sharing my story is one way to make sure others know they’re not alone.

Living Well With Diabetes and Hearing Loss

Diabetes and hearing loss are both invisible conditions that can deeply affect quality of life. Together, they can make communication, safety, and connection harder — but awareness and technology can bridge the gap.

The good news is that there are steps you can take to protect your hearing and strengthen your support system. Keeping blood sugar as close to your target range as possible may help, but the reality is that it isn’t always easy — and sometimes it’s beyond our control. Regular hearing exams, protecting your ears from loud noise, and reaching out to others who understand life with diabetes can make a real difference.

Protecting your hearing isn’t just about sound. It’s about connection, confidence, and living fully — with diabetes, with hearing loss, and with hope.

.jpeg)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)