T1D Guide

T1D Strong News

Personal Stories

Resources

T1D Misdiagnosis

T1D Early Detection

Research/Clinical Trials

Tegoprubart is a Game Changer in Islet Cell Transplantation Surgery for T1D Patients

A new immunosuppressant medication for islet cell transplant surgeries is reshaping the future of transplantation for people with type 1 diabetes (T1D). The drug tegoprubart has so far shown no serious side effects, unlike other immunosuppressants. In 2025, this combined drug-and-surgery approach is demonstrating promising success in the path to a cure.

.jpg)

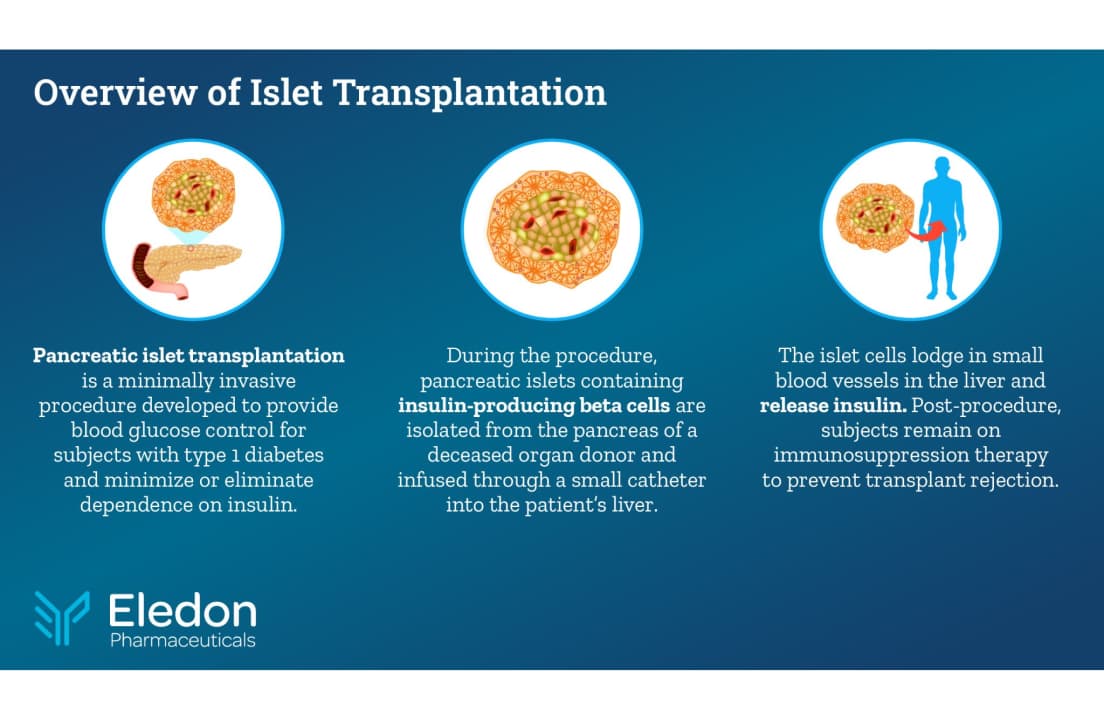

One positive advancement for people with type 1 diabetes who face life-threatening conditions like hypoglycemia unawareness, or severe hypoglycemic episodes, is islet cell transplantation, which involves implanting insulin-producing islet cells (sourced from donors or stem cell derivatives) into a patient’s liver.

The procedure requires lifelong immunosuppressive medication, which can pose health risks and, in some cases, undermine the very outcomes the treatment seeks to achieve. However, Eledon Pharmaceuticals’ development of tegoprubart is showing encouraging results.

In 2025, several patients with type 1 have documented their journey on social media after undergoing islet cell transplantation using tegoprubart. Chris, a 35-year-old with T1D who was diagnosed at 10 months old, posted that before transplantation, he required approximately 35 units of insulin per day, and three days after the islet transplant, his insulin needs had dropped to 13.7 units, using tegoprubart as the core immunosuppressant.

Additionally, one of the earliest trial participants, Marlaina Goedel, who had lived with type 1 diabetes for more than 25 years, underwent islet cell transplantation in 2024 after years of struggling with hypoglycemia unawareness. Within just four weeks, Goedel no longer required exogenous insulin. Today, she remains insulin-independent and continues the tacrolimus-free immunosuppression drug regimen—with tegoprubart at the core for over a year and a half.

T1D Strong had the privilege of speaking with Eledon CEO David-Alexandre Gros, M.D., and Piotr Witkowski, M.D., Ph.D, Director of the Pancreas and Islet Transplant Program at the University of Chicago Medicine’s Transplant Institute, about a groundbreaking, safer path for islet cell transplantation.

The Holy Grail of Transplantation

Aside from reaching the ‘holy grail’ of islet cell transplantation, which is achieving long-term, sustained independence from insulin injections without the need for lifelong immunosuppression, Eledon Pharmaceuticals’ tegoprubart brings us one step closer, according to Witkowski.

“The patients are doing much better so far, compared to previous patients; they feel better and have fewer side effects. The longest patient we have in this study has been on this medication for a year and a half, and she’s been off insulin.”

Until now, tacrolimus, a powerful immunosuppressant drug, has been used to prevent the immune system from rejecting transplanted organs.

Gros, who has served as Chief Executive Officer and a board member of Eledon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. since September 2020, noted that tacrolimus is used in approximately 90% of transplants (including islets, heart, lung, and kidney), but that its effectiveness comes with a range of side effects, including hypertension, tremors, and hyperglycemia.

New Immunosuppression, Less Side Effects

Witkowski told T1D Strong, “Tacrolimus has been the strongest medication to prevent rejection and the standard of care in organ transplantation. However, at the dose needed to protect organs from rejection, it’s toxic to the kidneys and the islets.”

With over 16 years of transplant experience, the renowned surgeon outlined clear patient benefits, confirming that tegoprubart has shown lower toxicity and fewer side effects in recent clinical trials funded by Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF) and The Cure Alliance.

With tegoprubart supplied at no cost by Eledon Pharmaceuticals, Witkowski performed the islet transplantation on nine enrolled participants at the University of Chicago Medicine’s Transplant Institute, in collaboration with the Diabetes Research Institute at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Beyond Insulin: Tegoprubart Trial Update

The minimally invasive surgery takes approximately one hour, during which the deceased donor-derived islet cells are infused into the patient’s liver. Witkowski added that the liver has a rich blood supply and ample space to accommodate the islets, which are actually small organs.

“Nine patients were transplanted using tegoprubart, and the next three are waiting for the donor islets, so hopefully soon,” said Witkowski.

After the transplantation, patients receive intravenous infusions of tegoprubart every three weeks as part of their immunosuppressive regimen.

Gros discussed the study’s positive outcomes, focusing on the reduction of severe hypoglycemic events in high-risk T1D patients. He highlighted that among the first six patients, there were no cases of severe hypoglycemia post-transplant, consistent with the FDA’s historical interest in demonstrating reduced hypoglycemia.

Success with Tegoprubart (Anti-CD40 Ligand)

In the past, many immunomodulators broadly suppressed the immune system, sometimes eliminating entire classes of white blood cells. Tegoprubart takes a more targeted approach, blocking the CD40–CD40L pathway to calm the immune response without widespread immune suppression.

According to Witkowski, nine trial participants (all classified with severe unstable glucose control) have received tegoprubart post-islet cell transplantation surgery and have achieved much lower insulin intake. In fact, many are insulin injection-free.

- Seven patients post-surgery are insulin independent, with three off insulin for over a year, including one with an A1c of 4.7% at 15 months.

- Three subjects were able to stop using insulin within three to four weeks after transplant.

- None of the patients experienced the severe toxicities associated with traditional immunosuppressive regimens (such as infections, blood clots, or organ toxicity).

- None of the patients experienced severe hypoglycemia episodes.

- Three patients required second transplants and have since maintained an A1c of 5.3%

(Additional islet transplantation is dependent on how much insulin the patient required previously. If a patient has a higher weight or higher BMI, they need more insulin and more islets.)

Replacing Tacrolimus with Tegoprubart

As well as the nine patients who’ve undergone islet transplantation with tegoprubart as the core immunosuppressant, one additional patient with CNI-associated nephrotoxicity was transitioned to tegoprubart from tacrolimus.

The goal is for tegoprubart to ultimately replace the far more toxic immunosuppressant, thereby enhancing the safety and therapeutic benefits of islet transplantation while substantially reducing side effects.

“The issue with tacrolimus is the safety; it comes with a wide range of well-known side effects,” said Gros.

Tacrolimus Long-Term Side Effects Include:

- Kidney damage

- Post-transplant diabetes

- Hyperglycemia

- Cardiovascular risks (hypertension and myocardial hypertrophy)

- Increased cancer risk

- Infections

- Neurological issues (tremors, headaches, or numbness)

- Blood disorders (risk of anemia and clotting)

“The number one complaint that patients have on tacrolimus is the neurological issues like tremors and brain fog,” said Gros. “It also causes cardiovascular effects like hypertension, and it’s toxic to pancreatic beta cells and kidneys.”

Tegoprubart is administered by infusion every three weeks, but Eledon is developing a subcutaneous formulation to improve patient convenience.

On the possibility of using tegoprubart to halt the progression of type 1 diabetes in stage 2 patients, Gros said, “Right now we’re looking at the potentially functionally curative rather than the preventative approach. It doesn’t mean in the future we might not go broader, but for now we’re focused on where we saw the greatest unmet need to have impact.”

In the past, people would need two to three transplants in a lifetime, and the goal of Eledon is “one transplant for life,” said Gros. Its three pillars of transplants are islet cells, kidneys and xenotransplantation.

At the end of 2025, Eledon announced that nine patients had received islet cell transplantation and were being treated with tegoprubart, including “eight patients that were de novo (patients receiving islets for the first time), and our first switch, a patient that had received an islet cell transplant, who was on calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus), but was not tolerating it,” said Gros. “The individual experienced tacrolimus-induced kidney damage, and to try to save that person’s kidneys, the physician elected to switch them to tegoprubart.”

Upcoming Tegoprubart Trial

A second tegoprubart study, funded by Breakthrough T1D and The Cure Alliance, is recruiting patients at the University of Chicago and the University of Miami. The subsequent trial will enroll T1D patients with severe hypoglycemia unawareness who also have kidney disease. Currently, such patients are ineligible for transplantation due to tacrolimus-related nephrotoxicity.

“We hope to prove that islet transplantation can reverse diabetes in type 1 patients with kidney dysfunction, which will be another milestone in this therapy,” said Witkowski. “The study will include 10 patients. And again, it’s a lot of money for just 10 patients. If the procedure is reimbursed, the same funding can serve 60-80 patients, and more will benefit, and we will learn much more.”

“These are patients with high-risk diabetes, something that is paradoxical, high A1cs, but at the same time, who get severe recurrent hypoglycemic events,” said Gros. “After seeing how the patients are doing, we hope to begin FDA discussions later this year.”

Funding for future trials depends heavily on FDA guidance in these discussions.

A Path Forward with FDA Guidance

Historically, the FDA wants to see efficacy, improved glucose control, fewer hypoglycemic events, and a reduced need for insulin injections.

“With data from our first six patients last year, we reported that we did not have a single case of severe hypoglycemia post-transplant,” said Gros. “We were able to achieve that quite quickly. Three subjects got off insulin within three to four weeks, and so far, safety has looked quite good in our first six patients, with no serious adverse events tied to tegoprubart.”

Witkowski added that FDA guidance is crucial to secure, because even if they enroll 30 patients per year across different protocols at centers nationwide, they can’t advance the field with such small numbers. “There are so many variables, there are so many things we can try at the same time, but we don’t have the opportunity and support for the patients now,” he said.

“If we have this drug approved and cells approved, we can do many more patients, faster, we can learn more and improve the field of transplantation without immunosuppression.”

ISLET Act

Many experts in the transplantation field have called for regulatory changes to reclassify islets. Witkowski explained that islet cell transplantation is still classified as research because the FDA regulates islets as a drug rather than an organ, a significant barrier to advancing more clinical studies.

“Islets are small organs. They should be regulated like any other organ for transplantation, for effectiveness, for patients’ safety, and for access to the therapy by the academic centers and the patients,” said Witkowski. “We’ve been working with senators to develop and pass the ISLET Act.”

The Increase Support for Life-saving Endocrine Transplantation (ISLET) Act is proposed U.S. legislation designed to reclassify pancreatic islets from FDA regulation as a “biological drug” to an “organ” for transplantation.

In other countries, including Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK, islet transplantation is considered standard of care and is often covered by national health systems.

“It’s a complex procedure that requires a lot of logistics, and the FDA is very rigid,” said Witkowski. “They are following the 1996 regulations, and say ‘we’re not going to change it,’ and this is the problem. We believe we have scientific evidence and that the regulations should be adjusted in the patient’s best interest, because if we stick to these regulations, we will not have therapy. We’ve been testing islets for 15 years, and we’ve spent millions of dollars funding islet transplantation research. We’ve proven it’s safe and effective.”

People can support the ISLET Act by contacting their senators and representatives to urge them to cosponsor and vote for the bill. Advocacy efforts include sharing information on social media, joining awareness campaigns, and highlighting personal stories to demonstrate the need for this treatment.

Future Collaborations & Why Expansion Matters

“I’m very excited with what we’re working on,” Gros said. “If you take a broader look, this concept of could there be a functional cure to T1D is now increasingly within our sight. I think it’s going to come from multiple places. We’re seeing innovation: one is the immunosuppressive aspect (with drugs like tegoprubart), and the second is research with islet cells.”

“Our goal is to collaborate with as many people as we can, so we’ll continue working on islet cell transplants at UChicago Medicine, supported by Breakthrough T1D,” he said. “Today, the field has donor-derived islets, and we hope tegoprubart will allow those cells to be used, and that could allow thousands of people in the U.S. to access cells.”

Over the past 15 years, researchers have begun pairing donor islet- or stem-cell-derived beta cells with encapsulation devices, cell pouches, and bio-hybrid organ systems, aiming to protect transplanted cells while reducing toxic immunosuppression.

“We have a collaboration with Sernova on their cell pouch, and then we’re doing a lot of work in xenotransplantation using pig organs in humans,” Gros added.

The Tradeoff: Lifelong Therapy, Life Changing Benefits

Currently, islet transplantation for T1D, whether using donor islets or stem cell-derived islets, is limited to patients with frequent severe hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness. Consequently, islet transplantation has the potential to reverse diabetes and allow patients to live insulin-free.

Patients require lifelong infusions, but the benefits include freedom from the constant fear of dangerous highs and lows in blood glucose, reduced risk of diabetes-related complications such as kidney, nerve, and eye damage, and a significantly improved quality of life.

Although these findings are still preliminary and based on a small number of patients, it’s promising that the pilot study is expanding enrollment. Such an advancement could broaden eligibility for the procedure, potentially allowing more patients to achieve long-term remission of type 1 diabetes.

“The most rewarding moments are when we can tell the patients they can stop insulin,” said Witkowski. “Seeing how happy they are is heartwarming for us, and then afterwards observing them without any side effects. This is what is driving us and giving us energy to do more and keep fighting for progress in the field.”

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).png)

.jpg)

.webp)